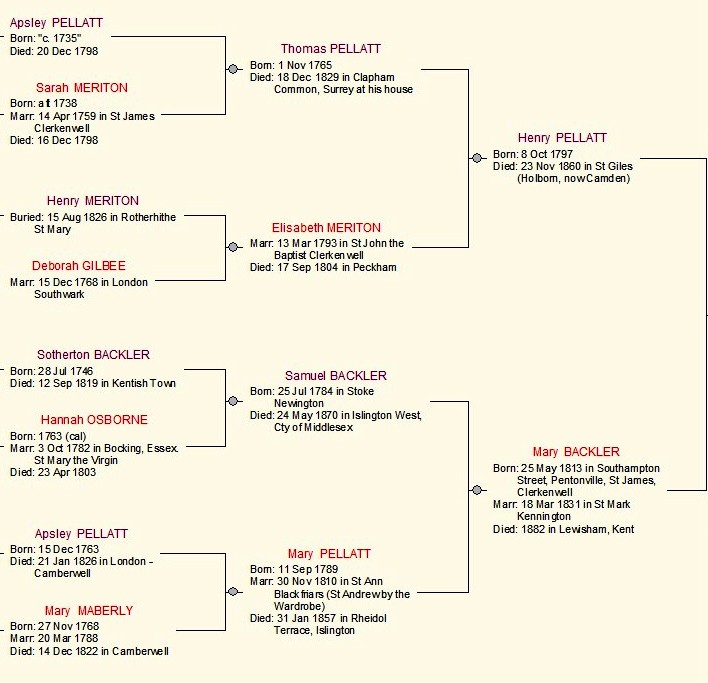

In which we meet Thomas Pellatt (1765-1829), Clerk to the Ironmongers, son of Apsley Pellatt II and Sarah nee Meriton, married to his cousin Elizabeth Meriton and father to Henry Pellatt, who married his cousin Mary Backler, as the diagram below attempts to show. We learn a bit more about the Ironmongers Company and note that the Pellatts showed nonconformist tendencies throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as did many of the Ironmongers.

The diagram above shows two generations in one line, ie Apsley Pellatt II is at the top left, while his son Apsley Pellatt III is at the bottom left and is the brother of Thomas Pellatt, top middle row. Hopefully readers get the gist!

We briefly met Thomas Pellatt in Post 50, noting he had been apprenticed Clerk to William Leeson and admitted free of the Ironmongers by patrimony in 1789. The Articles of Clerkship for his son Henry (see below) show that Thomas was ‘of Ironmongers Hall [by patrimony] in the City of London Gentleman and one of the Attorneys of His Majesty’s Court of Kings Bench Common Pleas and Exchequer at Westminster, and a Solicitor in the High Court of Chancery…’ He was also known to be ‘of Gray’s Inn’ .

He married his cousin Elizabeth Meriton by License at St James Clerkenwell in March 1795. They had four sons, baptised at Fetter Lane Independent Chapel, but for Thomas the future of his marriage and family were bleak. Three of the four sons died in childhood, with the deaths in Peckham of son Apsley Meriton Pellatt in 1803, aged nearly five, and young John (1800-1804), and in Brighton of first son Thomas in 1807, aged 11. He was buried there at the Union Street Meeting House and Ground – in what then was still known as Brighthelmstone. During those traumatic years, Elizabeth nee Meriton Pellatt died in Peckham in September 1804, perhaps in childbirth. This left just son Henry Pellatt, born in 1797 and articled for five years as Clerk to his father in 1815. We have already met him in posts 11 and 29, in which we traced some interesting relationships arising from the marriage and offspring of Henry and my many times great aunt Mary Backler, who had married in Kennington in 1831. I do not propose to investigate Henry any further.

Clerk to the Ironmongers Company: And so to the career and good works of Thomas Pellatt. Perhaps it was because he had precious little family that he seems to have thrown himself into a range of charitable and legalistic roles, primarily by his becoming Clerk to the Ironmongers Company in 1803, shortly before the death of his wife. He remained in this role until 1830, to be succeeded for four years by his son Henry. His name appears in many newspaper notices as signatory, Clerk of the Ironmongers. According to A History of the Ironmongers Company (Elizabeth Glover, 1991), Thomas Pellatt assumed the role of Clerk while the affairs of the Company were in some disarray. In his early years he fulfilled his legalistic and administrative duties efficiently, but according to Glover, ‘despite his excellent early work, Thomas Pellatt was .. to die with his affairs in disorder, and Henry Pellatt, the son who succeeded him for four years, was obliged to call upon his sureties, much to their indignation, for £343.2s.9d. in 1834’ (p. 105).

The Ironmongers were known for their charitable works, and for their Independent church leanings. On news of his death, the Trades’ Free Press on 26 December 1829 reported: ‘Died – a few days since, Thomas Pellatt, Esq., Clerk to the Ironmonger’s Company, Secretary to the Female Penitentiary, and Joint-Secretary of the Protestant Society for the Protection of Religious Liberty. The deceased was an eminently upright man, and a faithful friend to the various religious institutions which adorn and enlighten the country. His sudden death is greatly lamented by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance.’

Protestant Society for the Protection of Religious Liberty: In 1815, at the time of persecution of Protestants in the South of France, a very long letter in protest appeared in many newspapers around the country, signed by Thomas Pellatt and John Wilks, joint secretaries to the Committee of the above-mentioned Protestant Society, which had met at the New London Tavern, Cheapside on 21 November 1815, The Committee expressed their ‘astonishment and deep regret’ at learning of persecution in Nimes, and stressed their belief that it should be a matter of conscience for all people how they worship God. (See, for instance, Star, London, 30 November 1815)

IN 1825, Pellatt as Secretary to the Protestant Society wrote on their behalf to condemn the many Protestants who were petitioning against a Bill to remove the various disqualifications applying to Roman Catholics, stressing their overall belief that people should be free to worship according to their consciences. (See, for instance, Morning Herald, London, 2 May 1825) Later in the century, Apsley Pellatt IV, MP, would campaign on behalf of Jews.

London Female Penitentiary: The London Female Penitentiary was founded in 1807, and from the beginning, Thomas Pellatt was the ‘Gratuitous Secretary’. In 1817 he underwent a lengthy examination by the Metropolitan Police about the conduct, finances and more of the institution, reported on three days by the Morning Post – on 17, 18 and 23 December 1817. Thomas Pellatt stated the object of the institution was: ‘to afford an asylum to females who, having deviated from the paths of virtue, and who are desirous of being restored by religious instruction and the formation of moral and industrious habits, to a reputable situation in society.’

The word ‘Penitentiary’ derived from the 1779 Penitentiary Act, which focussed on deterrence and reform of miscreants, through religion, solitude and labour. Thus the ‘fallen women’ to whom Pellatt refers (who could have been prostitutes or sex workers, in modern parlance, but also any woman whose virginity was lost outside marriage). According to Pellatt, the people applying for admission were mainly ‘persons who have lived in service, maid servants, orphans, persons who have been left with one parent, and that parent being under the necessity of going out to work, they have been neglected and permitted to rova about the streets and with bad connexions with other females and other causes, have been led astray’. Pellatt reported ‘only some few of applications from the higher ranks’, and that the average age of admission was 17 or 18. One of the greatest causes of ‘this great evil’ was attendance at fairs: ‘We have more cases upon our books of women ruined at these nurseries of vice than of any other; those fairs I mean in the neighbourhood of the metropolis’.

Of the labour in which the women were occupied, Pellatt said: ‘Washing for hire, that is all the business of a laundry, to qualify them for service; making child bed linen and all kinds of needle work; spinning thread and worsted and knitting various articles, and general fancy works.’ The aim was to send women out to employment. But this was not a life of any luxury. The inmates had meat three times a week, on other days, soup, broth or pudding, and on Thursday, bread and cheese only, that being ‘the day on which the house is open for inspection of the public, and the sale of articles manufactured’. As for those leaving, unless dismissed for misconduct, women only left to go to employment after a maximum stay of two years, and there were more applications for servants than the institution could provide.

With the demise of Thomas Pellatt in 1829, it appears that his nephew Apsley Pellatt IV, son of Apsley Pellatt III and Mary Maberly (and brother to our very own Mary Pellatt) took over the role of Secretary. Apsley Pellatt IV was to become the famous glass maker and MP – much more of him later on.

I have tried in this post to give some flavour of the work of Thomas Pellatt, and more generally of the Pellatts as supporters of a range of liberal religious and charitable causes.

In my next post I will try to trace our Meriton line back a bit – it doesn’t go with any certainty beyond the early 19th century, but introduces a prosperous family in Bermondsey, south of the river Thames.

For an interesting piece on the London Female Penitentiary on Pentonville Road, see https://legalhistorymiscellany.com/2024/02/21/betrayed-seduced-trepanned-or-cruelly-driven-into-sin-the-london-female-penitentiary/