In which we discover – at last – the effigies of Humphrey and Ellen in Wilmslow Parish church.

As noted in previous posts, Humphrey and Ellen were commemorated in carved effigies resting in the Jesus Chapel of Wilmslow’s St Bartholomew’s Church. For some time my bucket list had included a visit to view these effigies in person, and the opportunity arose in the summer of 2023.

The church itself is an imposing and impressive structure, much changed since the Newtons’ day, when it was undergoing its first transformation from its 13th century origins under the direction of then-rector Henry Trafford. The Trafford family endowed the private Jesus Chapel where the Newton and Fitton effigies are to be found.

Deborah Youngs (Humphrey Newton (1466-1536) An Early Tudor Gentleman, The Boydell Press, 2008, pp 135-142) describes the effigies, placing them in the context of the Newtons’ status at the time. For instance, they are carved from sandstone, cheaper than alabaster, a more usual stone. And the effigies lie under a wall canopy which was probably recycled from the previous church, as were the carvings underneath the effigies. The Newtons were unlikely to have had the resources for freestanding tombs. Humphrey is clothed in a fur-lined civilian robe, relatively unusual at the time, when most effigies represented their subjects in military or ecclesiastical garb. Traces of red and black paint can still be seen. Ellen Fitton, represented as a widow, is simply dressed but, in recognition of her status as an heiress, lies closer to the east end and the altar than Humphrey, her head resting on a wheatsheaf, the symbol of the Fitton family. Neither effigy is meant to be a realistic representation of the subject.

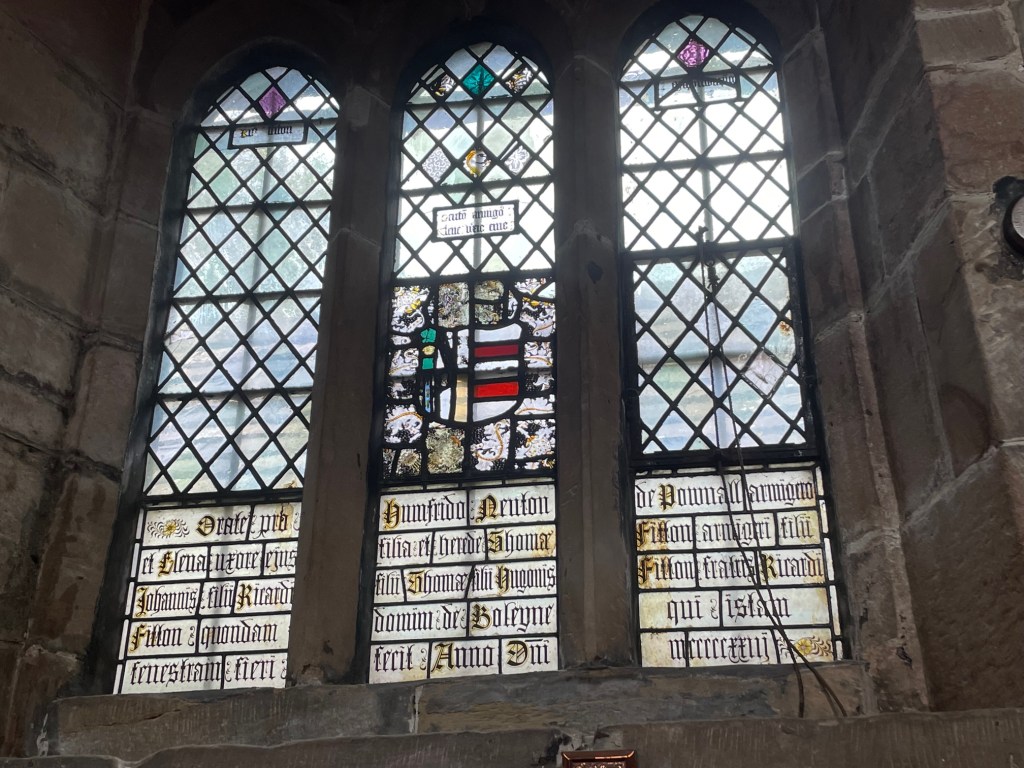

The two effigies lie beneath a window inviting prayers for Humphrey and Ellen, and setting out in some detail her Fitton ancestry. The images below show first, Humphrey and Ellen, then Humphrey, then Ellen, and then the window inviting prayers for them, showing her more distinguished descent.

It felt an astonishing privilege to stand right next to these nearly-600-year-old artefacts of my ancestry.

As part of establishing his position in society, Humphrey Sr set out his family origins in his commonplace book (see post 43). His findings saw marriages by male Newtons to women from landed families – Sybil Davenport, ‘of Davenport’, and Fenella Worth, ‘of Titherington’. Humphrey Sr’s great grandfather Richard (1336-1415) broadened family connections still further, divorcing his first wife and marrying Joan Barton, ‘of Irlam in Lancashire’. Oliver Newton was one son of this marriage, himself marrying well in 1428-9,to Alice Milton, who would be heiress to two landed estates. Rather shockingly to modern mores, it appears that Alice and Oliver were married when she was just 13, the canonical age of marriage being 12. According to Humphrey Newton, she brought with her links to the Earls of Chester, through an illegitimate line. Apparently the illegitimacy was less important than the lineage.

As part of establishing his position in society, Humphrey Sr set out his family origins in his commonplace book (see post 43). His findings saw marriages by male Newtons to women from landed families – Sybil Davenport, ‘of Davenport’, and Fenella Worth, ‘of Titherington’. Humphrey Sr’s great grandfather Richard (1336-1415) broadened family connections still further, divorcing his first wife and marrying Joan Barton, ‘of Irlam in Lancashire’. Oliver Newton was one son of this marriage, himself marrying well in 1428-9,to Alice Milton, who would be heiress to two landed estates. Rather shockingly to modern mores, it appears that Alice and Oliver were married when she was just 13, the canonical age of marriage being 12. According to Humphrey Newton, she brought with her links to the Earls of Chester, through an illegitimate line. Apparently the illegitimacy was less important than the lineage.