In which we meet the rather complicated Scheibel/Sheibell line, apothecaries from Friedburg, Wettaravia, Germany, naturalised as British citizens in the late 17th and early 18th centuries … but… they are not properly disentangled!

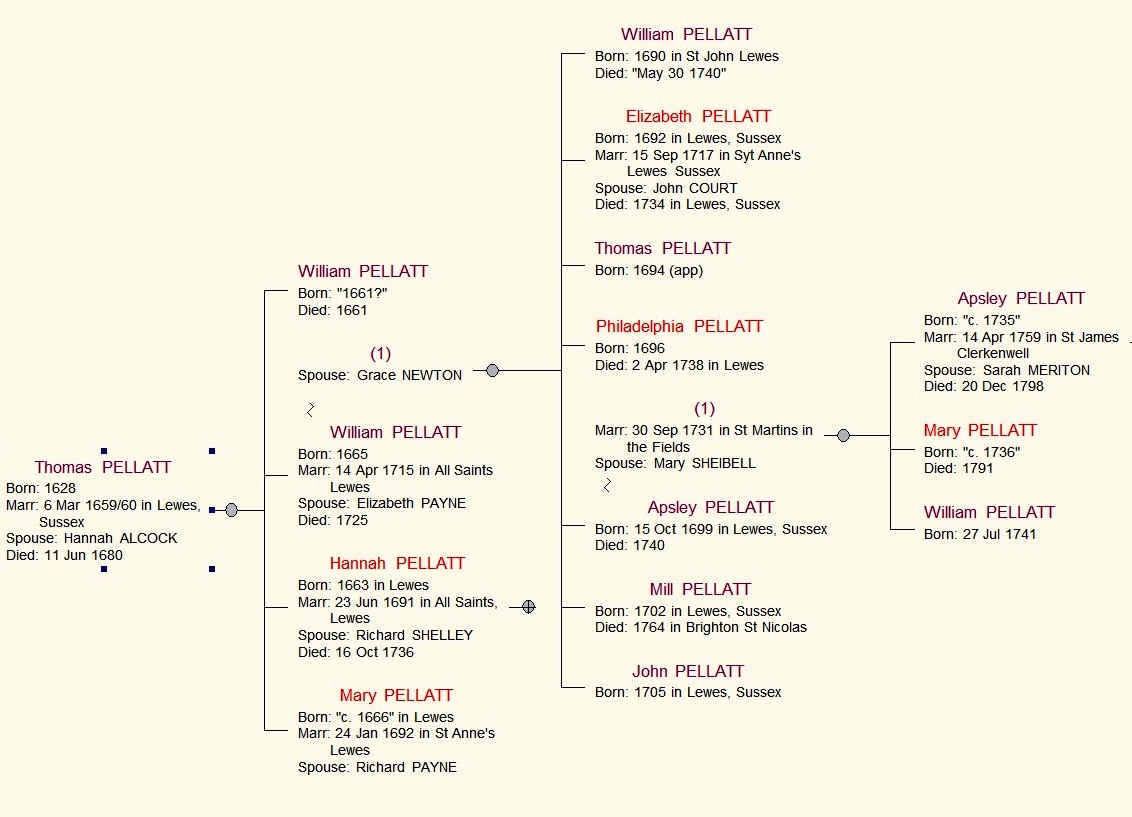

Two trees below show some pretty well known information, and some more speculative, derived from a variety of sources. The main person of interest for our purposes is Mary Sheibell (1712-1758), who married Apsley Pellatt (1699-1740/1). We are secure in the knowledge that Mary Sheibell was the daughter of John Sheibell ( – 1734) and Mary Houghton/Haughton ( – 1745). They married at St Martin in the Fields on 4 April 1706, and their four children’s baptisms are to be found in the parish registers of that church. Shown on the first tree below, they are Anne, born on 12 January 1707/8 and baptised on the 15th; a child Anne Sheibel [sic] was buried there on 5 February 1707/8, who could have been this Anne, or, feasibly, her cousin Anne Sheibell, daughter of Henry Sheibell and his wife Mary, who was born in November 1705. These Scheibells can be quite confusing. Next up for John Sheibell and Mary Houghton was John Sheibell, born 3 January 1709/10, and who died before 1745. He appears to have been somewhat troubelsome, as we will see when we look at his parents’ Wills. He had a daughter Mary by an unknown spouse. Then we come to Mary Sheibell, whose dates we have seen above, followed by the short-lived William Sheibell, who I believe was born and died in 1713.

Who was John Sheibell?

Looking at the trees below, we see that some sources show that Hartmann Scheibel, Apothecary, of Friedburg in Germany was the father of Henry Sheibell, Apothecary, and grandfather of John Scheibel, Apothecary, both of St Martin in the Fields. The naturalisation record for Henry Scheibel in 1693 clearly shows: ‘Henry Sheibell Son of Hartman Sheibell [1654-1723] and Katherine his wife born at Ffriedberg in Wetteravia in Germany’. After a certain amount of disagreement with the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, whom we have met many times before in our Backler stories, Henry was made free of the Society in 1691. He married Mary Peade, and a ‘tentative’ pedigree for him and a line for ‘our’ John Sheibell can be seen in Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica, London 1912, which can be viewed online at https://archive.org/details/miscellaneagenea4191bann/page/n39/mode/2up pages 8-10.

So far, so good, for Henry, but what about our John? The Pedigree shows him as Henry’s nephew, naturalised by Act of Parliament No. 94, 4 and 5 Anne (1706), as son of Mary Scheibel, father’s name not given. However, I have combed through the very many names of naturalised folk in this Act, and the one I find is ‘John Phillip Sheibell son of John Sheibell by his wife Mary born at Ffriedberg in Germany’. Is this ‘our’ John? I have reason to believe that it is, since John Phillip Sheibell was buried in 1734 at the Savoy Lutheran Chapel, and ‘our’ John (no Phillip in the name) died in that year, stating in his Will that he wished to be buried there. If this is so, and the Naturalisation parentage is accurate, ‘our’ John was indeed the nephew of Henry and the grandson of Hartmann. The trees below do not show his father as ‘John’, which I now believe to be the case.

Let’s see what else we know about our direct ancestor, John (Phillip) Sheibell ( – 1734).

Some years ago I explored the Vestry Minutes of St Martin in the Fields seeking information about John Sheibell and his son-in-law Apsley Pellatt. I am not sure how John Sheibell became a ‘Citizen and Apothecary’, but the Vestry Minutes consider in some detail the payments to John Sheibell in his role as apothecary to the poor of the parish, and later on, in his services to the workhouse:

‘This Board takeing into consideration an Apothecary to be employed this year by the Overseers of the poor for the relief of the poor, Doe recomend [sic] Mr John Sheibell, Apothecary to be employed by the Overseers of the Poor as Apothecary & Surgeon So as his Bills do not exceed Sixty pounds for & during all this year…’[1]

This recommendation was repeated in the following two years, but in 1720 the following entry appears:

‘John Sheibell Apothecary petitioned this Board complaining of the great Costs and Charges he yearly sustains by reason of his paying a Surgeon out of his Sallary of 60 £ y And, this Board taking the same in Consideration Ordered that the said John Sheibell’s Sallary be advanced to 80 £ y And during such time as the two Outwards shall remain part of this parish’[2]

The relationship of John Sheibell and the Vestry did not always run smooth. Cost-cutting is not just a modern phenomenon: at the Vestry of 13 September 1722, the Board apparently reviewed the salary and services, and decided that £60 a year should be sufficient to serve the Poor in Medicines and Surgery. If John Sheibell was not willing to accept these terms, then another should be elected ‘in his room’. But by Easter Monday 1723, his salary was £80, and in 1724, ‘A Memorial of Mr John Sheibell Apothecary for providing Medicines for the poor of this parish was produced for this Board and ordered to be referred to the next Vestry’ [although no mention of it is made at the next vestry].

More was to follow. In May 1725, on opening of the Workhouse, the Vestry

‘ordered and agreed that an Advertisement be put into the Daily Courant that if any sober, skilful Apothecary is willing to Settle at the Workhouse and to attend the poor of this parish He be desired to wait on Sr Jno Colbatch Knt at Bartram’s Coffee House in Church Court any Day between One and two in the afternoon to treat about the same’[3]

The upshot of this appeared to be that a Mr Kitchen was to be ‘imployed as Apothecary for the poor of this parish And to have 40 £ pa And Sallary for the same …’. This was followed by months of procrastination when the orders re Mr Sheibell and Mr Kitchen were referred over and over again to ‘the next Vestry’. Apparently John Sheibell wasn’t going to give up his position without a fight, and indeed, on Easter Monday 1726, John Sheibell was confirmed as Apothecary to the poor ‘provided his Bills exceed not 60 £ p. ann.’[4]

Following John Sheibell’s death in 1734, the Vestry Minutes of 15 April 1734 record the need for consideration of employing an Apothecary for the Service of the poor of the parish. Once again the matter was referred to successive Vestries, but finally (what happened to the care of the poor in the interim?), on 16 June 1735, it was:

‘Ordered and agreed that Mr Pellatt Apothecary be recommended .. to be .. employed for the service of the Poor of this parish for the remainder of this present year’.[5]

As we already know, Apsley Pellatt was John Sheibell’s son-in-law, having married Mary Sheibell in 1731. No further mention is made of Apsley Pellatt as Apothecary (nor indeed of anyone else). He died in 1740, and his wife married William Webb, who later became Churchwarden and Overseer.

Wills – a good source of information

We turn now to another key source of info for this Sheibell clan. The first Will of interest is that of Mary (nee Peade) Sheibell, wife of the above-cited apothecary, Henry Sheibell. He had died in 1723, but I have not located a Will for him. His wife, on the other hand, wrote her Will in 1730, and it was proved in 1732. She scattered any number of diamond rings and monetary legacies among her many children and grandchildren, but one item clarifies the relationship between her (and her late husband) and ‘our’ John Sheibell:

Item I give to my Nephew John Sheibell and to his wife Mary ten pounds apiece for Mourning and twenty shillings apiece more for a Mourning ring and to each of their children John and Mary I give ffive pounds for Mourning and twenty shillings apiece for a Mourning ring and I do further give and bequeath to my said Nephew John Sheibell a Legacy of one hundred pounds and in case he shall depart this life before my decease then I give the said one hundred pounds to his daughter Mary Sheibell and not otherwise

The Mary Sheibell in question, of course, is ‘our’ Mary who in 1731 would marry Apsley Pellatt.

We next move to the Will of John (Phillip) Sheibell, written in April 1732, and proved in April 1734. At the time of writing his daughter Mary will have married Apsley Pellatt, in 1731; the other surviving child is John, who is mentioned with some reservations in the Will, as follows:

I give and bequeath unto my only Son Twenty pounds and six Silver Spoons And in case my said Wife shall at any time after my death find and be satisfyed that my said Son John is reformed and become discreet and sober I recommend it to her to give to my said Son John the further sum of One hundred and Thirty pounds out of my Estate and Effects Also I give and bequeath to my Son in Law Apsley Pellett and to my dear daughter Mary his Wife Twenty pounds a peice [sic] and no more for Mourning I having given her a Portion upon her Marriage with the said Mr Pellet

After one or two other legacies, and specifying his wish to be ‘interred in the Vault or in the Church Yard of the Lutheran Church within the precinct of the Savoy with as little Ceremony and Expense as may be…’, he leaves everything else in the care of his wife, who he is sure will ensure it is used for the benefit of their children.

However, soon after – too soon, really – we come to the Will of Apsley Pellatt (1699-1740). Written on 11 March 1740 and proved on the 16th of the same month, he leaves all his property in Sussex to his wife Mary, the proceeds of which should be used for the maintenance and education of all their children, including the one ‘in ventre sa mere’ – not yet born (this is William Pellatt, born 1740/41, not sure what happened to him). Basically everything is left to his wife. She would re-marry after Apsley’s death, to William Webb, but I cannot find a Will of hers in 1758, when she died. However, we do have the Will of Mary (nee Houghton) Sheibell, her mother, and grandmother to the Apsley Pellatt children. Written in July 1745, and proved in August, she requests that she should be buried near her late son-in-law Apsley Pellat [sic], at St Martin in the Fields. Her wayward son John having died, she makes the following provision for his daughter Mary [mother’s name not known]:

‘I give and bequeath unto my grand daughter Mary Sheibell the only child of my son John Sheibell deceased the sum of two hundred and fifty pounds in satisfaction of a legacy of one hundred and thirty pounds which my late husband desired me to give to my said son John if I found him prudent and careful which said sum of two hundred and fifty pounds I direct to be paid my said granddaughter when she shall attain the age of one and twenty years or be married also I give and bequeath to my said granddaughter Mary Sheibell an old fashioned two handle silver cup and a gold ring set with ten diamonds one pair of silver salts six silver teaspoons and a strainer’

Apsley Pellatt’s children, Apsley (1735-1798) and Mary (1736-1791) were also given legacies:

I give and bequeath unto my grandson Apsley Pellat the sum of one hundred and fifty pounds also I give and bequeath unto the said Apsley Pellat a ribbed silver salver also I give and bequeath unto my granddaughter Mary Pellat one hundred pounds and a silver tea pot and I direct that the said legacies to my grandson Apsley Pellat and my granddaughter Mary Pellat shall be paid to them when and as they severally attain their respective ages of one and twenty years or be married…

Additionally to these legacies, however, came provision for her nephew John Stockwell (son of her sister Elizabeth and her husband John Stockwell), and apothecary Charles Carlisle to invest the sums left to the grandchildren and use the income to support their education and to put young Apsley Pellatt ‘apprentice to some genteel and reputable trade’. (See next post!) She left the rest and residue of her estate to her daughter Mary (Houghton Pellatt) Webb, for her sole use, which makes it puzzling that no Will can be found for her in 1758. Her husband William Webb died in 1771. He left most legacies to his daughters by his first marriage, but made son-in-law Apsley Pellatt (1735-1798) one of his Executors, and left £200 to be divided among Pellatt’s children when they reached age 21.

This rounds off our rather limited acquaintance with the Sheibells. Through Uncle Henry, there were any number of Sheibell descendants, but on ‘our’ John’s side there were only a few, one, Mary Sheibell (unknown mother), daughter of the wayward John, and ‘our’ Mary, mother of the second of very many Apsley Pellatts to follow. In the next post we will see this young Apsley Pellatt begin his association with the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, with which the Pellatts would have a long association.

All notes from Westminster Archives Centre: [1] WAC F/2006/4 Easter Monday 1717 [2] WAC F/2006/37 April 15th 1720 [3] WAC F/2006/183 May 3 1725 [4] WAC F/2006/224 [5] WAC F/2006/434