In which we face the sad task of reporting the complicated affairs of Samuel Backler and his wife Mary (nee Pellatt), as they faced bankruptcy and the loss of money and possessions, while looking after daughters Mary and Susannah Mary, and newborn Esther Maria. We glean most of the story from papers held at The National Archives in B/3/695: In the matter of Samuel Backler of St James Street, Piccadilly, Middlesex, tobacconist, bankrupt. Date of commission of bankruptcy: 1831 February 21

Our tale begins with a notice in The London Gazette dated 15 February 1831, to the effect that Samuel Backler, tobacconist of 81 St James’s Street, is unable to meet his financial obligations (https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/18776/page/302)

An insolvent debtor who was also a trader could declare himself bankrupt. An individual who was not a trader could be kept in a debtor’s prison, a fate which Samuel seems to have avoided.

Here began a process which stretched across the entire year, in which a parade of creditors (including close family) laid out their claims on Samuel’s assets, his wife Mary had to forego part of her inheritance from her grandfather Stephen Maberly, and at least some of the family’s furniture was sold. The date of 1831 was significant, as the process of administering bankruptcy was changing from Commissioners of Bankruptcy (which I believe was the process under which Samuel was treated) to a Court of Bankruptcy. I do not claim to be expert!

Information copied at TNA 26 September 2009. B/3/695. The information is mainly extracted. Where verbatim, it is in quotes. I have poor quality photos of further lists of creditors than are reported in this account – they are not usable, and so I have left them out. The total in debts was over £1,000, while money due to Samuel Backler was in the low £100s. The outcome of it all was that creditors were to receive £2 and 5s in the pound.

__________________________________________________

22 February 1831. Samuel Backler Tobacconist. Burwood Rooms George Maberly, Welbeck Street, Cavendish Square Middx. Coachmaker. Against Samuel Backler of St James’ Street Piccadilly in the County of Middx tobacconist. £104 – 17 – 4d lent between 1 January 1830 and 1 February 1831: ‘no security or satisfaction whatsoever’ except promissory notes and Bill of exchange.

Note: George Maberly was some sort of cousin to Samuel’s wife Mary Pellatt, though given the number of Maberly families in London at the time, I am not exactly sure of his relationship. George is probably the George Maberly who eventually became a partner in the famous firm of Thrupp and Maberly.

___________________________________________________________________

23 February 1830 [sic – is this 1831?]. George Cross of 3 Poole Street, Hoxton, Gentleman. Has known Samuel Backler four years, during which time he carried on trade, buying and selling tobacco, snuff, cigars and other commodities of a like nature. He said Samuel Backler was in insolvent circumstances and unable to meet claims of debtors. On Monday 14 February inst Samuel Backler came to Hoxton and asked for a bed because he was afraid of being arrested by his creditors for debt if he remained at his own house of residence. Samuel Backler stayed there until the present, having not returned to ‘his own house or place of business’.

_____________________________________________________________________________

22 February 1831. Provisional Assignment of Estate to William Burwood of Southampton Buildings Chancery Lane Gentleman. John Beauclerk, Jefferies Spranger and John Dyneley Esquires, the major part of Commissioners named and authorised in and by a Commission of Bankrupt – awarded and issued and now in Prosecution against Samuel Backler of St James’ Street Piccadilly in the County of Middlesex tobacconist. S.B. declared bankrupt at Burwood Rooms, 22 February 1831.

________________________________________________________________________________

22 February 1831 p. 350. London Gazette Giving notice of the following dates: 25 February, disclosure; 8 March – Assignees; 5 April – finish examination of creditors, agree certification. On this day Samuel Backler was reported as not at present prepared to make full disclosure and discovery of his Estate and Effects, praying further time until the next day. 25 February: Still not full disclosure.

______________________________________________________________________________

8 March 1831. List of Creditors:

- Gilbert Selioke Edwards, Newman Street, Oxford Street, Coachmaker. Late of Pall Mall. Executor Thomas Chamberlayne. Had loaned £25 10s

- Samuel Ward, Piccadilly, tobacconist. £100 – 10 – 10 for goods sold and delivered to Samuel Backler

- Henry Pellatt of Ironmongers Hall, Gentleman. £104 – 8 – 6 money lent and advanced on 25 May 1829, 25 January 1825, 7 May 1828. [on 18 March 1831, while these proceedings were going on, Henry had married his cousin Mary Backler, Samuel and Mary’s oldest daughter! They feature in several posts (and one forthcoming).]

- George Maberly, Welbeck Street, Cavendish Square, Coachmaker. £104 – 17 – 4

George Maberly and Henry Pellatt chosen as assignees

On this date, the solicitor’s bill of £40-8-2 to be paid from the first monies raised. Also the Messenger’s Bill, £14-4-8d

________________________________________________________________________________

5 April 1831. More creditors:

- Richard Vandome, Leadenhall Street, City of London, Scalemaker. £59 – 5s

- John Bale [Bask?] Derby Place, Bayswater in the County of Middlesex, Coal Merchant. Goods sold and delivered £14 – 16

_____________________________________________________________________

8 July 1831. London Gazette. P. 1382: ‘The Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt, bearing date of 21st February 1831, awarded and issued forth against Samuel Backler … intend to meet on the 29th of July instant at Eleven in the Forenoon, at the Court of Commissioners of Bankrupts at Basinghall-Street in the City of London in order to Audit the Accounts of the Assignees of the estate and effects of the said Bankrupt under the said Commission, pursuant to an Act of Parliament, made and passed in the sixth year of the reign of his late Majesty King George Fourth intituled “An Act to amend the laws related to Bankrupts.”

An untimely death: On 3 June 1831, Mary [Pellatt] Backler’s grandfather Stephen Maberly died in Reading. The timing of this death was rather unfortunate for Mary, in light of her husband’s bankruptcy proceedings! Stephen Maberly had made specific provision for his grandchildren in his Will, which was proved on 5 July 1831, with quite a few Codicils relevant to the Backler bankruptcy. Having initially left £4000 in trust for the benefit of ‘all and every the child of my late daughter Mary Pellatt’ [Samuel’s mother-in-law], this sum was reduced to £2500 in a codicil, which excepted Mrs Mary Backler. In an earlier Codicil, dated 12 August 1826, there was to be deducted £250 from ‘Mrs Backler’s share of the property I have left to her, having lately advanced that sum for her husband’ but that Codicil was revoked on 26 April 1827 in favour of the following:

£400 on trust – interest, proceeds etc – to Mary Backler into her own hands for her sole and separate use exclusively of her present and any future husband and without being liable to his debts or arrangements. On her death, proceeds to go to every her child and children when they become 21, or when the daughters marry.

This inheritance results in a notice on August 22: The Law Advertiser, Vol. 9: Special meeting of creditors of bankrupts:

‘Backler, Samuel, St. James’s-st., Piccadilly, Middlesex, tobacconist; Sept 21, at 12 precisely, C.C.B., as to assignees compromising their claim to a legacy of 200l, bequeathed by Stephen Maberley, deceased, to the bankrupt’s wife, by accepting half of such legacy, and permitting the remainder to be settled on bankrupt’s wife for her separate use; and on other special affairs.’

Some confusion? I am not sure how the legacy of £200 was determined. In his Will Stephen Maberly had declared the legacy of £400 to be free from any debt of her husband. Was this £200 Mary’s share of the £2500 left to all the children of Mary [Maberly] and Apsley Pellatt? I don’t fully understand, as I thought she had been exempted from this. Apparently not (see below). Perhaps the £400 would remain at the disposal of Mary.

At the Court of Commissioners of Bankrupts, Basinghall Street London 21st day of September 1831: Memorandum – At a Meeting of the Creditors and Assignees of Samuel Backler of St James’s Street Piccadilly in the County of Middlesex Tobacconist Dealer and Chapman a Bankrupt held on the day and year and at the place above written pursuant to a notice in the London Gazette of the thirtieth day of August last in order to [sic] the said Creditors to assent to or dissent from the said Assignees compounding their claim to a Legacy of £200 bequeathed by the Will of Stephen Maberly late of Reading in the County of Berks Esquire deceased to the Bankrupt’s Wife by receiving one half of the said Legacy and allowing the other half to be retained by the Trustees or Executors under the said Will for the purpose of Settlement on the said Wife of the Bankrupt for her separate use according to the decisions in Equity in like Cases And further to assent to or dissent from the assignees paying to a party to be named at the meeting the amount of certain premiums paid by him on a policy of Insurance in the London Life Association effected on the life of the said Bankrupt for the sum of £500 with a view to the Assignees obtaining possession of the said Policy And also to assent to or dissent from the said assignees selling and disposing of the said Policy and of any other the Estate and effects of the said Bankrupt either by public auction or private contract and for such terms and prices as they shall think fit And also to assent to or dissent from whatsoever the said Assignees hitherto done or at the said Meeting shall propose to do in reference to the said Bankrupt’s Estate.

The following is a copy of a letter from Mr Apsley Pellatt [Mary Backler’s brother] to the assignees produced and read at the Meeting –

“Mr Apsley Pellatt presents respects to the Assignees of Samuel Backler and acquaints them that he is willing to surrender to the use of the Creditors the Policy of Insurance of His (Mr B’s) life of £500 in the London Life Assurance Office on payment of the premium (he has paid) amounting to £27.13.10 Mr Apsley Pellatt begs also to say that he has no doubt on the Creditors assenting to accept £100 in full satisfaction of the Legacy of 1/11th of £2500 left by Will by the late Stephen Maberly Esquire to Mrs Backler that the Executrix will forthwith pay the same into the hands of the Assignees”. Falcon Glass Works. 17 Sept 1831

Present the undersigned Creditors

It was resolved and agreed that the said assignees be authorized to pay to Mr Apsley Pellatt the Sum of £27. 13. 10 the amount of the premiums paid by him on the above mentioned Policy And that they be at liberty to dispose of the said Policy either by Surrender to the London Assurance Office or by Public Sale or private contract and at such price and on such terms as to the said Assignees may seem meet

Secondly – It being stated at the meeting that the Legacy in question being to the Bankrupts Wife and that the Court of Chancery thro’ which alone such Legacy could be recovered always makes a provision for the Wife out of it, and generally to the extent of one half of the Legacy, It was resolved and agreed that the said Assignees be also authorized and empowered to receive the sum of £100 in full satisfaction of their claim of the Legacy of 1/11th of £2500 left by the Will of the late Stephen Maberly Esquire to Mrs Backler the Wife of the Bankrupt and that they also be authorized to give and sign full and sufficient receipts and discharges for the same

Thirdly – and resolved and agreed that the undersigned do approve of the sale of the Bankrupts Furniture as made by the assignees, and ratify the same accordingly.

Henry Pellatt. Richard Vandome. Sam Ward

________________________________________________________________________________

22 November 1831. London Gazette. P. 2442. Notice of the following event: The Commissioners ‘intend to meet on the 23rd day of December next, at Ten of the Clock in the Forenoon … in order to make a Dividend of the estate and effects of the said Bankrupt; when and where the Creditors, who have not already proved their debts, are to come prepared to prove the same, or they will be excluded the benefit of the Dividend. And all claims not then proved will be disallowed.

Account: Cash realised:

Sale of bankrupt’s furniture £20/3

Cash in compromise of Stephen Maberly legacy £100/ –

Deposit on sale of policy per Mr Shuttleworth £24/-

Balance from the purchases [?] £96/–

£240/3-

Paid:

30 Sep Solicitor’s bill re choice of assignees £40 – 8 – 2

Mr Pellatt’s claim re life policy £27-13-10

Mr Shuttleworth’s charge on sale of policy £6 – 0 – 0

Messenger bills £20-14-8

Auctioneer charges sale of furniture £4 – 14 – 0

Solicitor dividend £49-13-10

Claim of shopman in full £5 – 10

Claim of maidservant in full £3 – 0 – 0

Balance to be divided £82-8-6

£240 – 8 – 0

____________________________________________________________________________

23 December 1831: More debts!

- Richard Cater, deceased. 17 September 1827 £23-8-4

- William Deighton 71 St James’s Street Tailor. Goods

sold and delivered. Work and labour done as a tailor £22 – 1 – 6 - Maria Palmer 8 Kensington Terrace, Kensington

Gravel Pits late servant to the Bankrupt. Wages due.

Her X. £3 – 0 – 0 - John Martin, 82 St James’s Street, tailor. Goods sold

and delivered. £6 – 19 - William Cousins, 45 Duke Street, St James’s. Carpenter

Carpentry work £6 – 12 – 5 - James Davies, 106 New Bond Street, late shopman to

The Bankrupt. For wages £5 – 10 – 0 - John Collier, Carey Street, Lincolns Inn, Gent.

By judgement HM Court Kings Bench, Easter term

11th year King George IVth for £500 debt and 65

shillings costs. Indenture re William Nokes [Noke?] £203

________________________________________________________________________________

23 December 1831. Creditors to get £2s 5d to the £

_______________________________________________________________________________

What to make of all this? Little more is heard of Samuel Backler before his death in 1870, other than his presence in the 1851 and 1861 Censuses and the marriage of his second daughter Susannah Mary Backler to James Boulding in 1844. We do not know what happened to Samuel and Mary after the traumatic events of Samuel’s bankruptcy in 1831, other than to assume that it did little in terms of good family relationships! Clearly Samuel was a poor businessman. Was he reckless, or just unfortunate? We may never know.

In which we consider the life and early career of my 3x great grandfather, Samuel Backler, having reviewed the varied fortunes of his four half-siblings and nine siblings in previous posts. We follow Samuel as he embarked on a career as an apothecary, like his father, grandfather and half brother John before him. We see his fortuitous marriage to the eldest child of noted glassmaker Apsley Pellatt, and after what seems to have been an abortive apprenticeship, we witness Samuel setting up in business, perhaps armed with inside knowledge of the market for Peruvian Bark from his and his father’s association with the Society of Apothecaries.

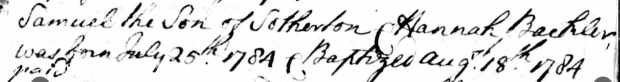

In which we consider the life and early career of my 3x great grandfather, Samuel Backler, having reviewed the varied fortunes of his four half-siblings and nine siblings in previous posts. We follow Samuel as he embarked on a career as an apothecary, like his father, grandfather and half brother John before him. We see his fortuitous marriage to the eldest child of noted glassmaker Apsley Pellatt, and after what seems to have been an abortive apprenticeship, we witness Samuel setting up in business, perhaps armed with inside knowledge of the market for Peruvian Bark from his and his father’s association with the Society of Apothecaries.  Early years: an apothecary apprentice and laboratory worker. Samuel Backler was the second child and oldest son of Sotherton Backler (1746-1819) and his wife Hannah Osborne (approx 1763-1803). He was born in Stoke Newington, and baptised at St Mary’s Church there. (The church, left, is ‘the old church’, no longer consecrated.)

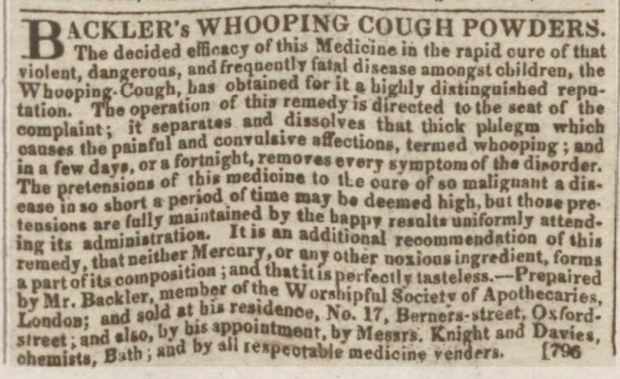

Early years: an apothecary apprentice and laboratory worker. Samuel Backler was the second child and oldest son of Sotherton Backler (1746-1819) and his wife Hannah Osborne (approx 1763-1803). He was born in Stoke Newington, and baptised at St Mary’s Church there. (The church, left, is ‘the old church’, no longer consecrated.) Bedford Street Laboratory: Following his marriage, Samuel set up his lab at Covent Garden’s Bedford Street. Here he marketed a range of interesting lotions and potions, such as this one for Asthmatic Strontium Tobacco (The Morning Post, 10 October 1811). Backler was in the forefront of the use of stramonium, derived from the common thorn-apple, in treating asthma. The history of the use of smoking in treating asthma is fascinating, and can be explored through the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2844275/

Bedford Street Laboratory: Following his marriage, Samuel set up his lab at Covent Garden’s Bedford Street. Here he marketed a range of interesting lotions and potions, such as this one for Asthmatic Strontium Tobacco (The Morning Post, 10 October 1811). Backler was in the forefront of the use of stramonium, derived from the common thorn-apple, in treating asthma. The history of the use of smoking in treating asthma is fascinating, and can be explored through the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2844275/ suggest that for a while, at least, Samuel, adept at trading on the name of Apothecaries’ Hall, pursued a successful career marketing medicines from his laboratory in Covent Garden and later from his home in Berners Street. To modern eyes, his claims of quality and efficacy make interesting reading indeed!

suggest that for a while, at least, Samuel, adept at trading on the name of Apothecaries’ Hall, pursued a successful career marketing medicines from his laboratory in Covent Garden and later from his home in Berners Street. To modern eyes, his claims of quality and efficacy make interesting reading indeed!