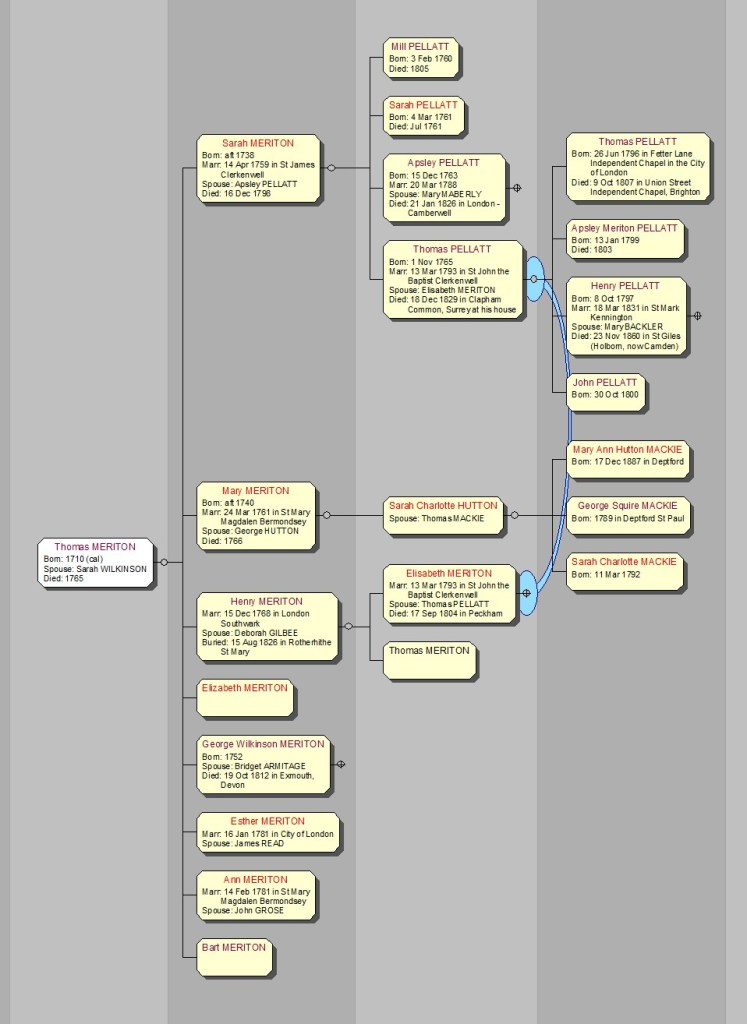

In which we meet the parents of Sarah Meriton (1739-1798), wife of Apsley Pellatt (1735-1798). Six-times great grandparents Thomas Meriton ( -1765) and Sarah Wilkinson ( -1784) had eight known children whose fates we will briefly consider in our next post. But firs,t a quick look at some of the quite complicated relationships, including that of Sarah’s short-lived sister and brother-in-law, and their three children.

On the left of the tree we find Thomas Meriton ( – 1765) and his wife Sarah Wilkinson (- 1784). More about them in a minute. Of interest in the next generation down are, of course, oldest child Sarah Meriton (1739-1798), wife of Apsley Pellatt II (1735-1798) , and mother of Apsley Pellatt III (1763-1826). He in turn, with wife Mary Maberly (1768-1822), was father of 15 children – too many to show here! – including their oldest child, Mary Pellatt (1789-1857), who married Samuel Backler (1784-1870) – the Backlers being the starting point of this whole blog! Stay with this, because there are some cousin relationships coming up. (See https://backlers.com/2017/03/21/samuel-backler-1784-1870-family-thefts-and-a-changing-career/ )

Sarah nee Meriton and Apsley Pellatt II are also parents of Thomas Pellatt (1765-1829), who married Elizabeth Meriton ( – 1804), the daughter of Sarah’s younger brother Henry Meriton ( – 1826). Thomas Pellatt and Elizabeth were parents of, among others, Henry Pellatt (1797-1860), who married Mary Backler (1813-1882), daughter of Mary Pellatt and Samuel Backler. (See:https://backlers.com/2025/08/27/51-thomas-pellatt-1765-1829-clerk-to-the-ironmongers/ ) (See also https://backlers.com/2014/11/06/thomas-meriton-pellatt-or-sargeant-who-is-the-father/ )

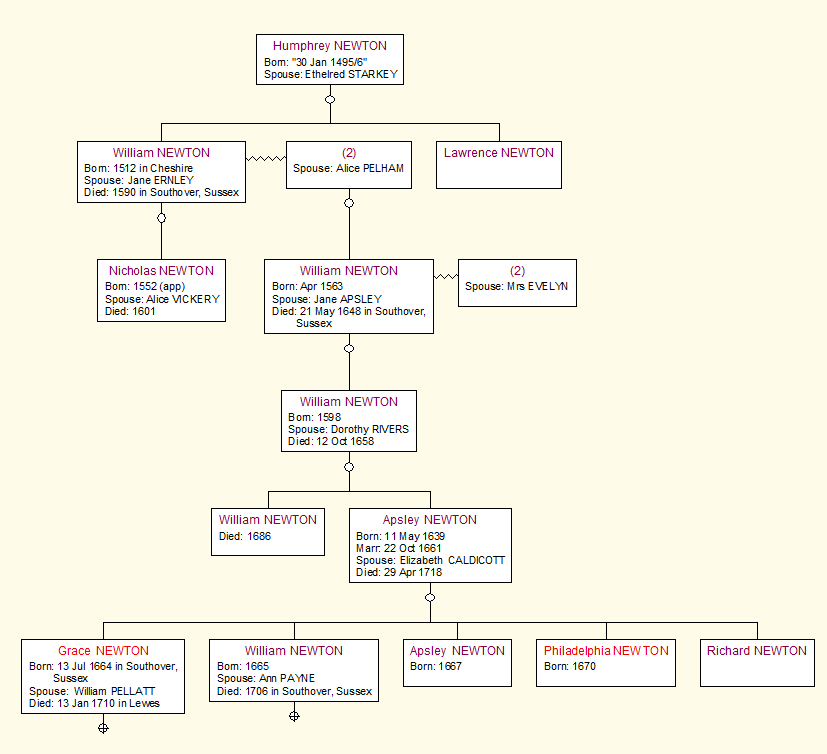

Meanwhile, as I was making final preparations for this post, I reflected with some frustration that I had little information about Sarah Wilkinson’s origins. So I decided to try once more to find parents, using as a starting point the name of her brother, George Wilkinson Meriton -= surely named after his grandfather? And yes, so it proved. The story below of variously interconnected families is largely drawn from the Wills of the key players.

Thomas Meriton ( – 1765). Origins? Here I have found pretty much of a dead end. Various online trees show a christening at St Sepulchre London on 27 May 1710 of a Thomas Meriton, father Thomas, Mother, Elizabeth. Another possibility is the christening of a Thomas Merriton [sic] at Greenwich St Alfege, on 2 December 1696 to Henery Merriton and Johannah. Thomas and Sarah’s first son was named Henry. But I cannot find a Will or other evidence which would confirm either of these. So Thomas’ origins remain doubtful for the moment.

Rather more satisfying – at least one generation back – is the find of George Wilkinson ( – 1762) of Clerkenwell. As noted above, a search on Wills for George Wilkinson threw up one in Clerkenwell, where at St John the Baptist, Sarah Wilkinson ‘of this parish’ had married Thomas Meriton ‘of St Olave’s Southwark’ on 5 February 1731. This George Wilkinson Will was incredibly obliging. Written on 28 November 1759, it tells us that George was an Ironmonger of St James, otherwise St John, Clerkenwell. After certain bequests (see below), all the rest, residue, real and personal estate etc etc are left to ‘my Son in Law Thomas Meriton‘, sole executor of the Will. Rather handily, and just to make sure of our family connections, two of the three witnesses were Apsley Pellatt [II] and Sarah [nee Meriton] Pellatt. How satisfying! [The bold typeface throughout this post indicates my direct ancestors.]

Root: George Wilkinson‘s Will began with a bequest which aroused my curiosity. The very first Item reads: ‘I give to my Grand Son Samuel Root and to my two Grand Daughters Elizabeth Root and Ann Wilkinson Root the sum of One hundred pounds each’, when married or they reach age 21…and Thomas Meriton is appointed their Guardian. So, in 1759 when the Will was written, there were three children of a daughter of George Wilkinson, who seemed to be orphaned. Here is how it works: George Wilkinson had two daughters, Sarah (who married Thomas Meriton in 1731) and Elizabeth, who married widowed Mason Samuel Root in St Benet, Paul’s Wharf in 1748. Guessing back from their marriage dates, I infer that Sarah was born around 1711, and Elizabeth perhaps much later – perhaps with a different mother than Sarah? Their father George Wilkinson was widowed when he married widow Sarah Bart, also at St Benet Paul’s Wharf in 1731. (This historic Wren church is just north of the River Thames, opposite Southwark and Bermondsey. I am not sure why these marriages took place there.) I have not found an earlier marriage for George, nor have I found a baptism for either daughter.

But, back to the sad Root story. There are baptism records for Elizabeth (1750-1763), Samuel (1751-1764) and Ann Wilkinson Root (1752 -). Sadly, we find a Will for their father Samuel Root of the Parish of St Mary Magdalen Bermondsey, Citizen and Mason of London, written just five years after his marriage to Elizabeth, on 4 October 1753, and proved on 15 October 1753. Samuel appoints three executors – ‘my honoured father Roger Root of the Parish of St John [Horsleydown] in Southwark Carpenter, my father in law George Wilkinson of the Parish of St James Clerkenwell Ironmonger and my brother in law Thomas Meriton of the said parish of St Mary Magdalen…Ironmonger to be joint executors’…; After debts etc, everything is left to loving wife Elizabeth Root, the three children, ‘and such other child or children as my said wife is now pregnant with…’ The usual provisions are made for education and maintenance of the children.

So, one of the Executors was George Wilkinson, whom we have seen died in 1762. What about wife Elizabeth (nee Wilkinson) and the other grandfather, Roger Root? Well, he died in 1755, when only one son proved his Will as executor, since the other Executor, son Samuel, had already died. And Elizabeth? By the time of George Wilkinson’s Will, written in 1759, she is not mentioned. Nor is there a fourth child. I wonder if she died in child birth. This leaves just one Executor – and Guardian.

Thomas Meriton’s Will: And so we turn to Thomas Meriton. His Will was written on 28 January 1764 and proved by the sole Executrix, his wife Sarah nee Wilkinson Meriton on 6 November 1765. It makes no mention of the Root children, who are still minors. Why? Well, I think Elizabeth died in 1763 – there is a burial in Bermondsey for a 13-year-old Elizabeth Root. I think Samuel was buried in May 1764 in Bermondsey, brought from St John Horsleydown, in nearby Southwark, where there were Root relatives. But I am not sure about Ann Wilkinson Root, who was baptised on 12 November 1752 in Bermondsey. Presumably she was with some family member.

I think I will leave the rest of Thomas’ Will, and that of his wife in 1784, until my next post, where both Wills will introduce us to their many children. The Meritons were a prosperous family, he seeming to have been a successful Ironmonger, and she, perhaps, having inherited property and other things from her father, George Wilkinson. Considerable sums of money and jewels, and much property, feature in the Wills, as well as something of a mystery surrounding a child named Bart Meriton.

1861 England Census. St Pancras, Camden Town. 3 Pratt Street (see photo right)

1861 England Census. St Pancras, Camden Town. 3 Pratt Street (see photo right) Back to the Cross family.

Back to the Cross family.

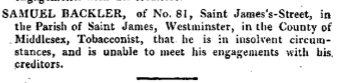

In which we consider the life and early career of my 3x great grandfather, Samuel Backler, having reviewed the varied fortunes of his four half-siblings and nine siblings in previous posts. We follow Samuel as he embarked on a career as an apothecary, like his father, grandfather and half brother John before him. We see his fortuitous marriage to the eldest child of noted glassmaker Apsley Pellatt, and after what seems to have been an abortive apprenticeship, we witness Samuel setting up in business, perhaps armed with inside knowledge of the market for Peruvian Bark from his and his father’s association with the Society of Apothecaries.

In which we consider the life and early career of my 3x great grandfather, Samuel Backler, having reviewed the varied fortunes of his four half-siblings and nine siblings in previous posts. We follow Samuel as he embarked on a career as an apothecary, like his father, grandfather and half brother John before him. We see his fortuitous marriage to the eldest child of noted glassmaker Apsley Pellatt, and after what seems to have been an abortive apprenticeship, we witness Samuel setting up in business, perhaps armed with inside knowledge of the market for Peruvian Bark from his and his father’s association with the Society of Apothecaries.  Early years: an apothecary apprentice and laboratory worker. Samuel Backler was the second child and oldest son of Sotherton Backler (1746-1819) and his wife Hannah Osborne (approx 1763-1803). He was born in Stoke Newington, and baptised at St Mary’s Church there. (The church, left, is ‘the old church’, no longer consecrated.)

Early years: an apothecary apprentice and laboratory worker. Samuel Backler was the second child and oldest son of Sotherton Backler (1746-1819) and his wife Hannah Osborne (approx 1763-1803). He was born in Stoke Newington, and baptised at St Mary’s Church there. (The church, left, is ‘the old church’, no longer consecrated.) Bedford Street Laboratory: Following his marriage, Samuel set up his lab at Covent Garden’s Bedford Street. Here he marketed a range of interesting lotions and potions, such as this one for Asthmatic Strontium Tobacco (The Morning Post, 10 October 1811). Backler was in the forefront of the use of stramonium, derived from the common thorn-apple, in treating asthma. The history of the use of smoking in treating asthma is fascinating, and can be explored through the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2844275/

Bedford Street Laboratory: Following his marriage, Samuel set up his lab at Covent Garden’s Bedford Street. Here he marketed a range of interesting lotions and potions, such as this one for Asthmatic Strontium Tobacco (The Morning Post, 10 October 1811). Backler was in the forefront of the use of stramonium, derived from the common thorn-apple, in treating asthma. The history of the use of smoking in treating asthma is fascinating, and can be explored through the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2844275/ suggest that for a while, at least, Samuel, adept at trading on the name of Apothecaries’ Hall, pursued a successful career marketing medicines from his laboratory in Covent Garden and later from his home in Berners Street. To modern eyes, his claims of quality and efficacy make interesting reading indeed!

suggest that for a while, at least, Samuel, adept at trading on the name of Apothecaries’ Hall, pursued a successful career marketing medicines from his laboratory in Covent Garden and later from his home in Berners Street. To modern eyes, his claims of quality and efficacy make interesting reading indeed!