In which we use the Wills of Thomas Meriton and his wife Sarah nee Wilkinson to build a picture of their circumstances and family members.

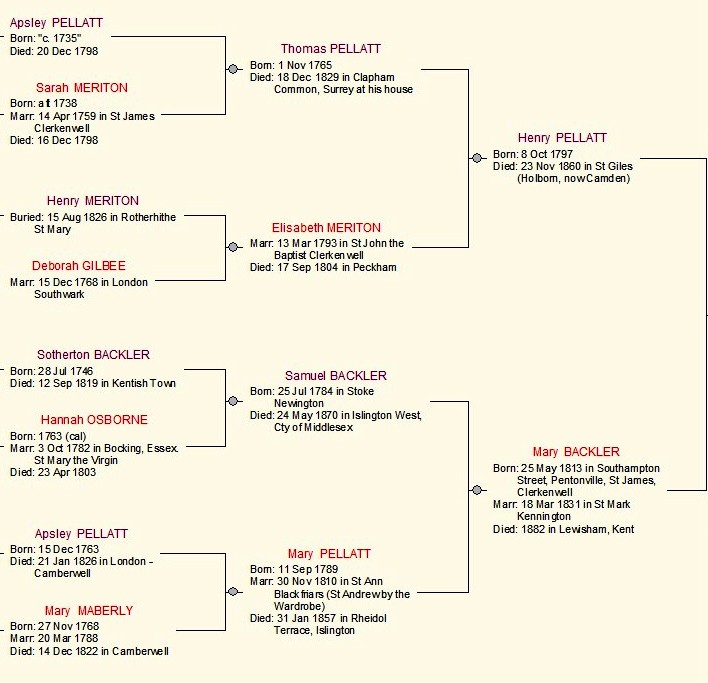

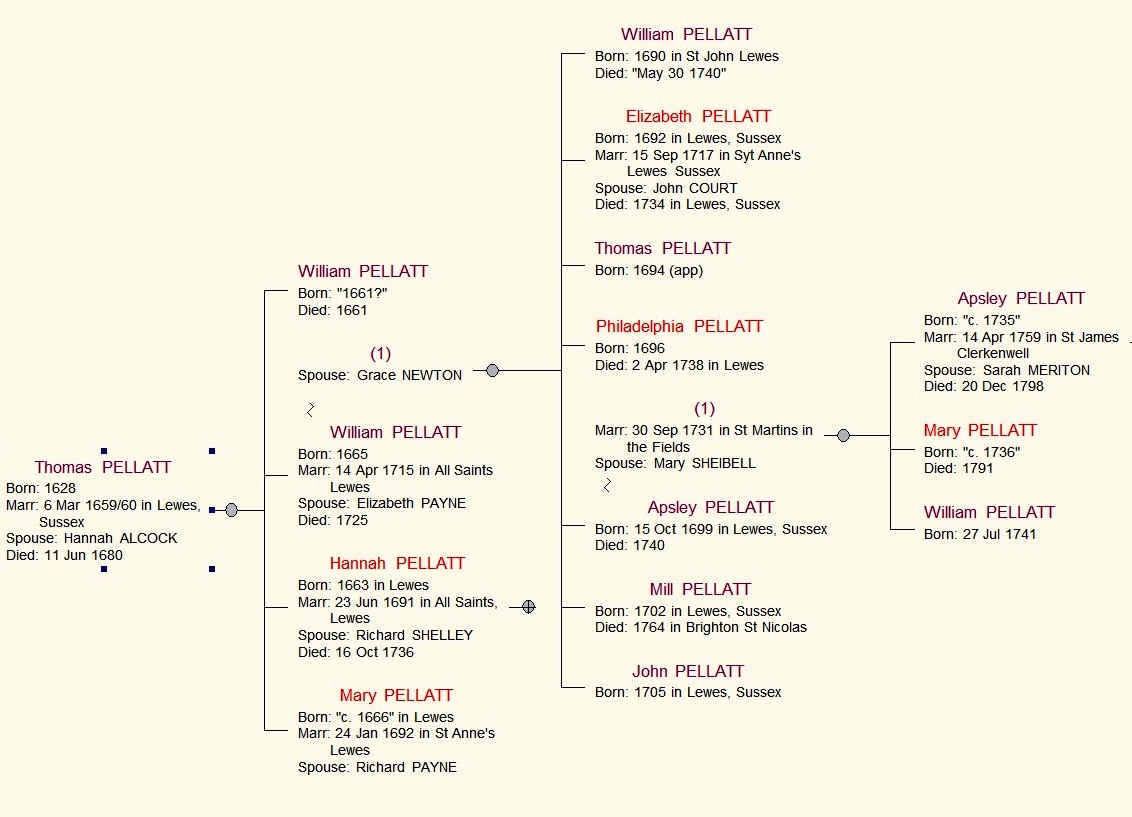

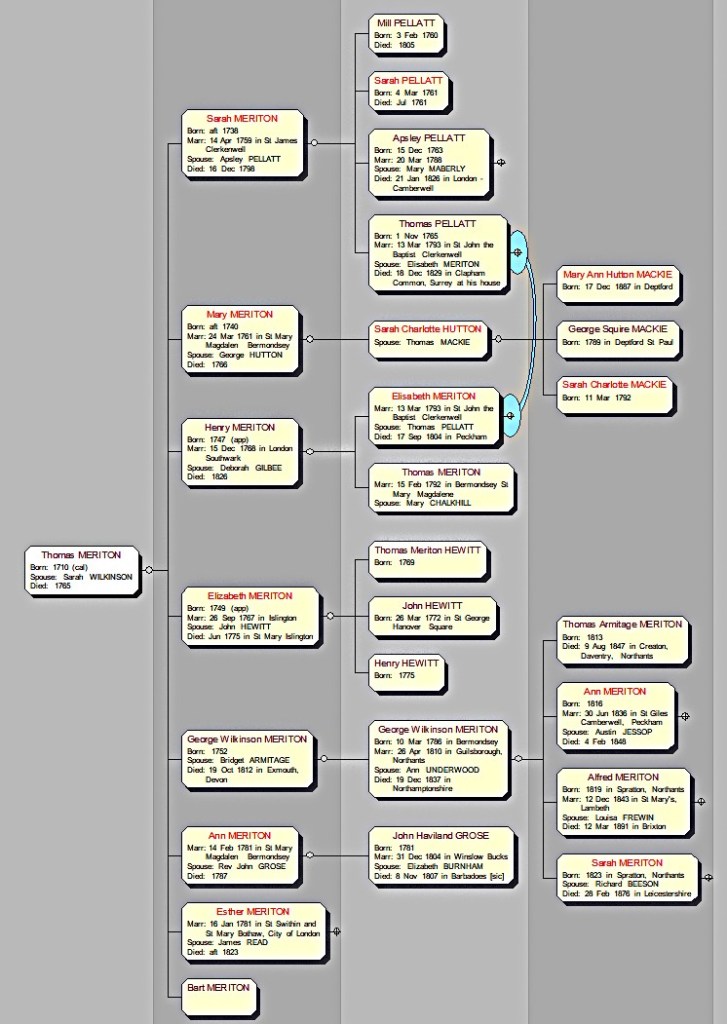

The tree below is similar to that in post 52. This time it omits Pellatt descendants, and includes descendants of Sarah [nee Meriton] Pellatt’s siblings, so far as they are known to me.

In this post, I plan just to use the Wills of Thomas Meriton and his wife, Sarah nee Wilkinson, to introduce readers to the various descendants and other relatives of this partnership. This was a prosperous merchant family resident just south of the River Thames in Bermondsey. In later posts we will follow the very varied lives of each of these branches.

Many years ago, when I had the zest for such things, I extracted key points from the two Wills in question. I use these extracts now. First up is Thomas Meriton, who pre-deceased his wife by nearly 20 years

PROB 11\914 28 Jan 1764 Proved 6 November 1765

Thomas Meriton Of the Parish of St Mary Magdalen Bermondsey Ironmonger

To son Bart Meriton one annuity or yearly sum of £25 from the day of death by wife as she sees fit for his support and maintenance for his natural life ‘in full Bar of all his Claims or Demand into any further or other part of my Estate I having sufficient reasons for so doing’

Bart Meriton is a bit of a mystery. He appears here with this carefully worded legacy, but I have not found a record of his baptism, which I think would have been around 1738, given that he was apprenticed to a Turner, Thomas Fowell, in 1752. A Bart Meriton married in Warwickshire in 1766. Could this have been him? More in the next post.

To son Henry Meriton all that my Messuage Dwelling House or Tenement with the Warehouse Yard Ground Wharf and Appurtenances thereunto belonging situate lying and being at or near Dockhead in the said parish together with the Lease whereby I hold the same premises for and during the rest of the unexpired term, he paying the Rent and performing the Covenant therein Contained on the Tenant or Lessees part to be paid done and performed

Further to Henry ‘all the ffixtures which shall then be in about or belonging to the said premises together with all my Weights Scales and all other my utensils and Implements which are used and employed in and about my said Trade or Business of an Ironmonger and also such part of my Goods or Stock in Trade as upon a just and true valuation and appraisement to be had and taken shall amount to the full Sum or value of five hundred pounds Sterling’ But if it falls short, Executors should make up the amount in ready money to Henry, and if it shall be more than £500 value, and Henry wants to take some or all of it, he should deliver a Bond or Obligation to the Executrix within three years, and the sum repaid with annual interest of four per cent until it is paid off.

Eldest son Henry Meriton seems to benefit from the whole of Thomas Meriton’s business interests. A n online search for the value of £ 500 from 1765 to the present day yields a result of something over £ 100,000.

To each of four children: Elizabeth Meriton, George Wilkinson Meriton, Esther Meriton, Anne Meriton £500 stock in bank annuities bearing interest at four per cent or five hundred pounds to each of them in money, as Executrix thinks fit when they attain 21 or the daughters marry provided marriage is with approval of Sarah Meriton (wife). Otherwise the Legacies shall not be paid to them my said daughters or to such of them as shall marry contrary to the Approbation and good liking of their said Mother until she or they shall attain their said several full Ages of twenty one years anything aforesaid to the contrary notwithstanding

Legacy to George Wilkinson Meriton shall be fully paid to him when he attains his said age without any deduction or abatement thereout for any sum of Money that may be given to place in forth Apprentice it being my will and mind that the same shall not be accounted as or for part of his said Money

Sarah Meriton shall take the Interest etc of my said four childrens several Legacies for and towards their Board Maintenance Cloathing and Education and bringing up in their several Minorities. If any one of them should die before full age or marriage then the Legacy of that person shall go to wife Sarah Meriton

To my aunt Sarah Smith of Greenwich in Kent one annuity or yearly sum of £5 for her life, paid quarterly

To my son in law Apsley Pellatt and to my daughter Sarah his wife £20 apiece for mourning

To my son in law George Hutton and my daughter Mary his Wife £20 apiece for mourning

To my cousin Thomas ffowell of London Merchant and Sarah his wife £10 apiece for mourning

To my friend Abraham Harman of Shad Thames in Southwark Scrivener £10 for mourning

Sole Executrix Sarah Meriton and all the rest residue after above legacies plate jewels money stocks rings household furniture and everything else to her to be disposed of at her death of her own free will provided she remains a widow sole and unmarried. In case she shall marry again then ‘I give and bequeath unto my said Wife Sarah Meriton only one thousand pounds Bank Annuities bearing interest at four per cent or one thousand pounds in Cash which of them my said wife shall think fit to accept and take and all my household goods plate Rings Jewels Linnen Pewter Brass China Ware and all other my household ffurniture whatsoever part of my residuary Estate and all the rest residue and remainder thereof in case of such Intermarriage again of my said Wife I give devise and bequeath order direct and appoint shall be unto and for my seven children Sarah Pellatt Mary Hutton Henry Meriton Elizabeth Meriton George Wilkinson Meriton Esther Meriton and Anne Meriton’ to be divided among them that are living share and share alike

And if my wife should marry again, I constitute my said cousin Thomas ffowell and my ffriend the aforenamed Abraham Harman to be Trustees and Guardians for my younger children during their several Minoritys

28 January 1764. Witnesses Wm Hart and Wm Harman in Shad Thames. Proved in London 6 December 1765 by oath of Sarah Meriton relict of the deceased

Wasn’t he well off? The premises in Dockhead remained identified as Meriton’s Wharf well into the 19th century. Note that Bart is not mentioned again, and that Thomas clearly didn’t think his wife Sarah should marry again. His ‘cousin’ Thomas ffowell is, I surmise, the Turner to whom Bart Meriton was apprenticed in 1752. We will meet the youngest offspring and their various spouses in the Will of Sarah Meriton (nee Wilkinson) to which we now turn.

Sarah Meriton [nee Wilkinson] Will PROB 11/1112 3 September 1783 Proved 20 January 1784

Sarah Meriton of Mill Street in the Parish of Saint Mary Magdalen Bermondsey in the County of Surrey Widow

First ‘I forgive and release unto my Son in Law Apsley Pellatt the sum of ffive hundred pounds which he is indebted to me by two Bonds under his name and seal and which said two Bonds I order and direct my Executors … to deliver up unto the said Apsley Pellatt to be cancelled and made void’

Also bequeath £200 to said Apsley Pellatt to be paid within one month after death

‘I forgive and release unto my son Henry Meriton all Sum and Sums of Money owing by him to me on Bond or otherwise except the Sum of One Thousand and five Hundred pounds lent by me to him and for which he hath executed a Bond and also a Mortgage of the Messuage or Tenement Warehouses Yard Ground Wharf and Appurtenances thereunto belonging situate in Mill Street aforesaid’ and all but this one to be delivered to him and cancelled and made void’

‘I forgive and release unto my son George Wilkinson Meriton £200 owing to me upon his Bond…’ etc as above

‘I also give and bequeath to my son George Wilkinson Meriton the sum of ffive hundred pounds as part of the Mortgage Money which I have on the premises in Mill Street…’

Also give him my great Silver Waiter [?] Silver Coffee Pot and the Case with the Silver Knives and fforks therein and also the Counterpane of my own work

‘I also give to my Daughter Sarah the wife of the said Apsley Pellatt my best Diamond Ring the two pictures of my self and my late husband with my Silver punch Bowl

All my other plate I give to my two daughters Hester [aka Esther] the Wife of James Read and Ann the Wife of the Reverend Mr Grose to be divided share and share alike

To three daughters Sarah Hester and Ann my wearing apparel equally divided between them

To Hester Read the Mahogany Chairs the Seats of my daughter Hewit’s work [She was Elizabeth Meriton, 1749-1775, who predeceased her mother]

To Ann my Gold Watch and two Mahogany Chairs, seats of my own work

To Son George Wilkinson the fire screen of my Daughter Hewit’s work

To Apsley Pellatt and his wife Sarah Pellatt twenty pounds

To son Henry Meriton and Deborah his wife Twenty Pounds

To James Read and Hester his Wife Twenty Pounds

To the said Reverend John Grose and Ann Twenty pounds

Ten pounds apiece to son George Wilkinson and Grand Son Thomas Meriton Hewitt [sic]

All other household furniture and Implements, Linen China etc equally divided share and share alike to Hester and Ann and to son George Wilkinson

To Grand daughter Sarah Charlotte Hutton Twenty Pounds for Mourning

To Grandsons Mill, Apsley and Thomas Pellatt Ten pounds apiece for mourning

To Mrs Sarah Buxton and to Mr Suggett and his wife a Mourning Ring each

‘To William Row of Aldermary Church Yard in the City of London Skinbroker and to my son George Wilkinson Meriton all that Messuage or Tenement with the Ground and Appurtenances thereunto belonging situate in Cold Bath Fields in the County of Middlesex and known by the Sign of the Anchor to hold the same unto the said William Row and my said son…’ for the remaining unexpired term on trust for the sole and separate benefit of my daughter Sarah Pellatt during her life …’ so as not to be in any wise subject to the Debts Contraul [sic] or Engagements of the said Apsley Pellatt and after her death the rents and profits etc (if the leases are still continuing)’ should be for son Henry and after him to son George Wilkinson Meriton

In some way payment from the Cold Baths properties is to be made of one hundred pounds apiece to three grandsons Thomas Meriton Hewitt, John Hewitt and Henry Hewitt when they are twenty one

Give and bequeath to William Row and son George Wilkinson Meriton ‘all these my Messuages or Tenements with the appurtenances in Turks Head Yard in the Parish of St John Clerkenwell in the said County of Middlesex to hold for the rest of its term and by and out of the rents and any profits thereof to pay an annuity or yearly sum of twenty pounds to son Henry clear of all deductions and abatements by quarterly payments – into the proper hands of son Henry and not any other person or persons. After the annuity ends, then to use and benefit of two daughters Ann and Hester

All the rest and residue to William Row and George Wilkinson Meriton one moiety to be invested and benefit Hester, after her to any of her children, reverting to her siblings

The other moiety invested and to benefit Ann

Mill St Property mortgaged to Isaac Buxton and his wife – they should have £200 per year plus interest til it is paid off

Executors William Row and George Wilkinson Meriton

Signed 3 September 1783. Probate 20 January 1784

I have not managed to identify William Row, nor have I found further information about Sarah’s property in the Clerkenwell area. It seems likely it would have derived somehow from her father? We have already noted that Apsley Pellatt’s ironmongery business was also in the area of St John’s Clerkenwell. It would appear that the widowed Sarah had managed to retain a genteel lifestyle as her children matured and married. We will briefly look at their fates in subsequent posts.