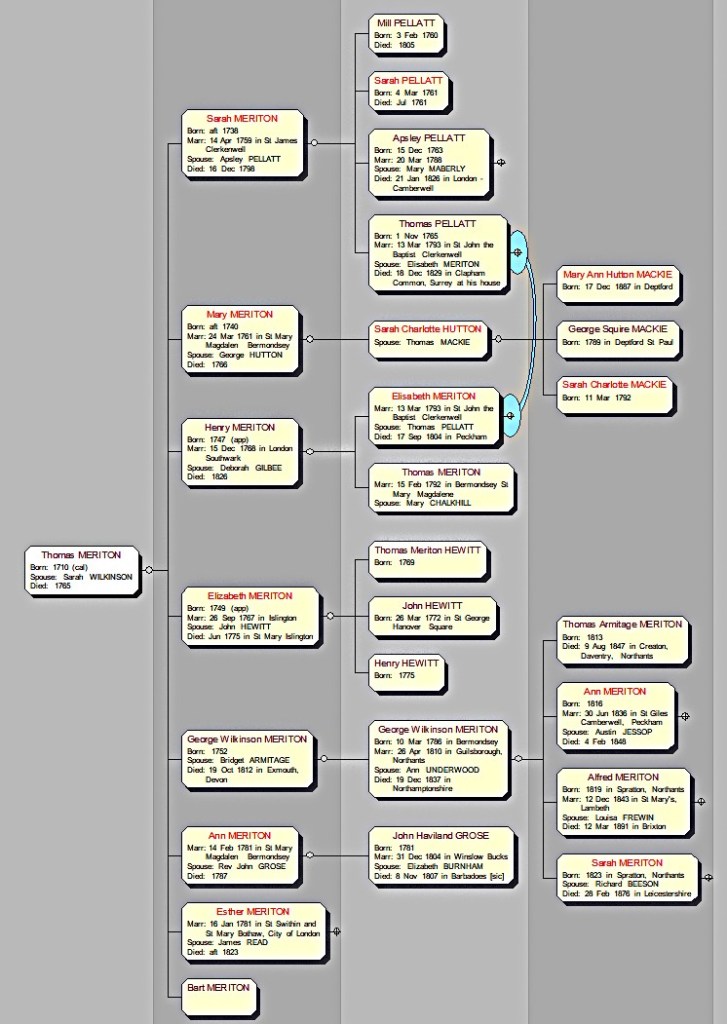

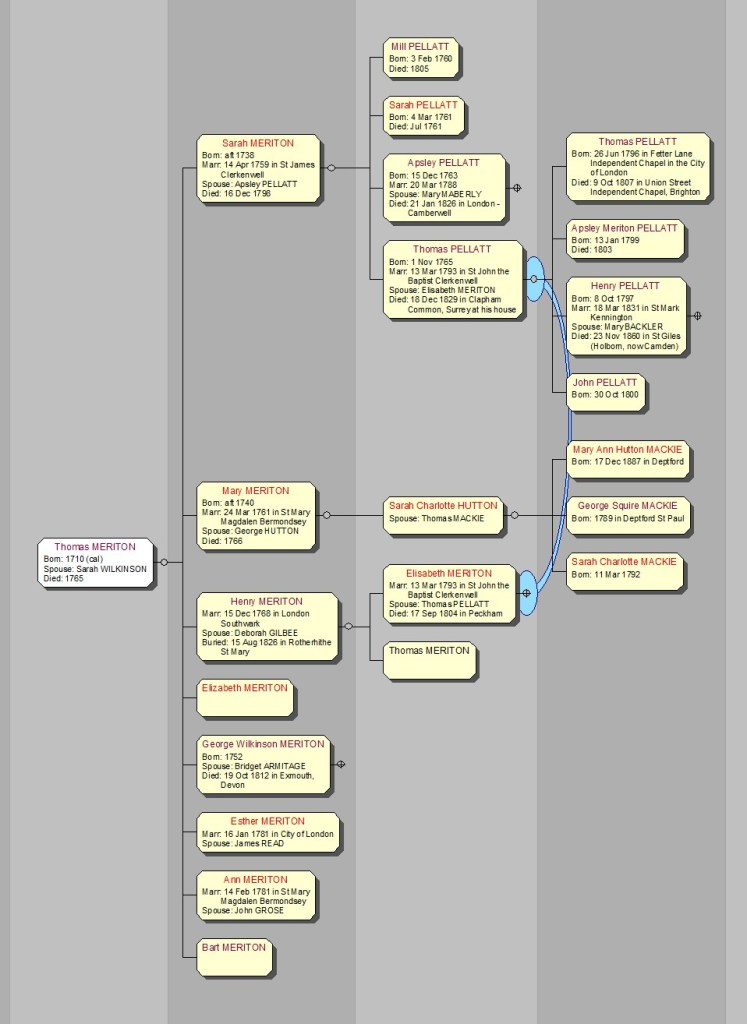

In which we unpick some recent searches yielding further information about the origins of Thomas Meriton (?1710-1765) and his son Bart (?1738 – ?). Apprenticeship records offer clues as to their identities.

St Sepulchre and Snowhill lie north of Holborn Bridge, as described in the following extract from John Strype’s ‘A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster’ 1720:

In my previous post I noted that ‘our’ Thomas Meriton, ironmonger of Bermondsey, who died in 1865, was shown in some Ancestry trees to have been baptised in 1710. I had reservations, not seeing any link between ‘our’ Thomas and his putative father located north of the Thames. However, now I am converted and set out my thoughts here.

The Baptism Register of St Sepulchre, Newgate, shows Thomas Meriton baptised on 28 May 1710 to Thomas and Elizabeth Meriton in Nags Head Court, Snowhill. There is a similar baptism entry for John Meriton on 5 October 1707 and I have seen a written record for a Robert Meriton, son of Thomas and Elizabeth, on 13 December 1717.

| St. Sepulchres Church, or St. Sepulchres in the Baily, seated on the top of Snow hill; a very large and spacious Church, with a lofty Towered Steeple, Spires at each corner, and Weathercocks on the tops. In which Steeple is a gallant ring of eight Bells; and in the Church is a pair of Organs. To this Church there is a large Churchyard both before and behind it; although not so large as of old time, good part being taken away, and converted into Buildings; so that now it is not enough for the burial of their Dead; and the Inhabitants are forced to make use of another large piece of Ground in Chick lane. | St. Sepulchres Church. |

| Robert Lewis, Leather-seller, gave to this Parish 30l. a Year for Coals to the Poor. | Benefactors. |

| Robert Dove, Merchant Taylor, gave 50l. for the Prisoners Bell. The Meaning is, that when the Condemned Prisoners are drawn to their Execution at Tyburn, there is a Man with a Bell, who stands in the Churchyard, by the Wall next the Street, and so tinkles his Bell, and repeats some Verses, to put them in mind of their Death approaching. |

| This Church was very much ruined in the late dreadful Fire; but by the Money raised from the Imposition on Coals, and the Charges of the Parishioners, and Benefactors, it is Rebuilt, and beautified both within and without. |

| Next to this Church is Sarazen’s Inn, very large, and of a considerable Trade for Wagons, Coaches and Horses. | Sarazens Inn. |

| Church lane, adjoining to this Church Eastwards, which leadeth into Pye Corner; noted chiefly for Cooks Shops, and Pigs drest there during Bartholomew Fair. | Pye Corner. |

| Nags head Court, long and ordinary. And opposite to this is Green Dragon Court, which is but small. |

Extract from https://www.dhi.ac.uk/strype/TransformServlet?page=book3_283

A superb website hosted by the University of Sheffield, containing many digitised resources. Content can be used through Creative Commons. The home page for this project can be seen at https://www.dhi.ac.uk/strype/index.jsp

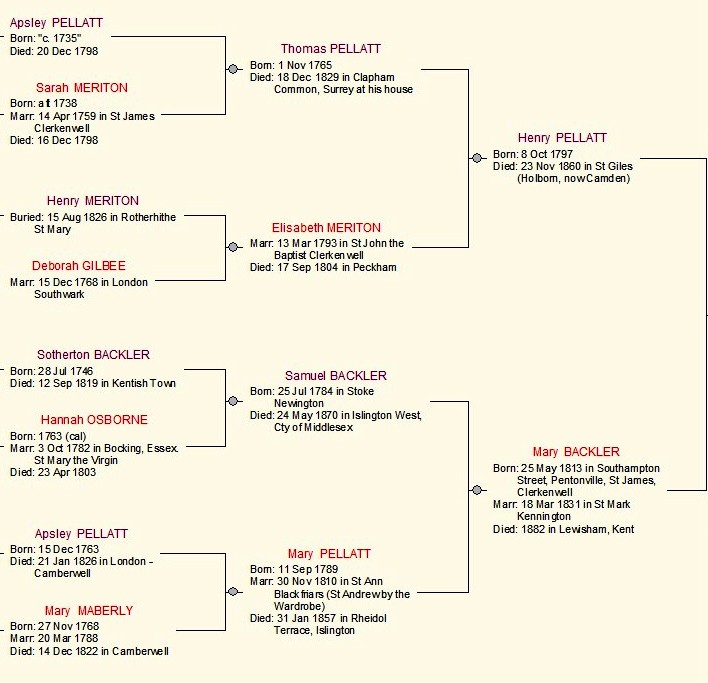

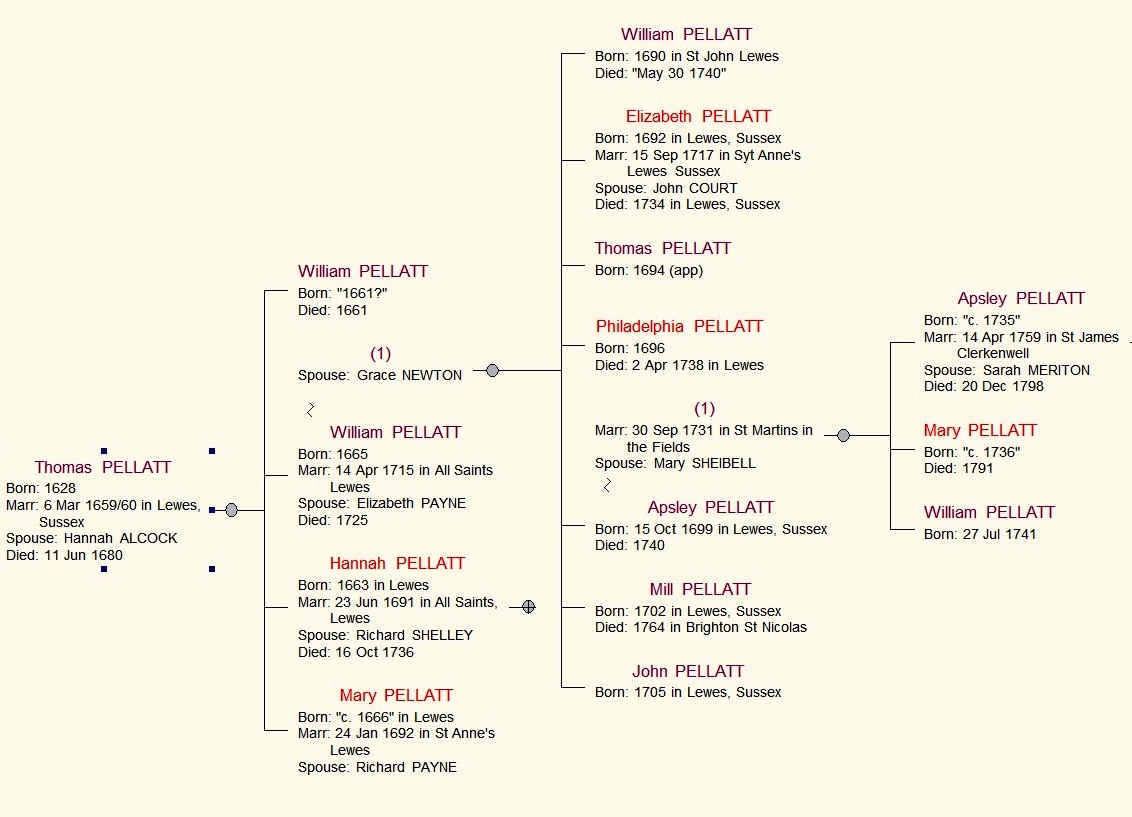

It then seemed wise to hunt for a marriage of Thomas Sr to the Elizabeth Howson whose name appeared on various Ancestry trees. This proved to be the same couple as that mentioned in the baptisms above: At St Nicholas Cole Abbey, a church still standing in the City of London, Thomas Meriton and Elizabeth Howson were married on 10 October 1700. He was of the Parish of St Sepulcries London[sic], a Turner on Snow Hill. She was of the Parish of St Botolph Aldersgate. One more fact attracted interest – the marriage was conducted by ‘Mr Merriton’, who turns out to have been the longstanding Rector of this church, and surely related in some way to our protagonists. He can be found on the CCED website ( https://theclergydatabase.org.uk/jsp/search/index.jsp ), son of Henry and brother of John, and even warranted a mention or two by Samuel Pepys ( https://www.pepysdiary.com/encyclopedia/10516/#references ), but I have not managed to link him directly with ‘our’ two Thomases. He was buried at St Nicholas Cole Abbey in 1704/5.

So, we now have ‘our’ putative Thomas Jr being the son of Thomas, a Turner. We can now use the London and Country apprenticeship records on Findmypast, where we find links which I believe bring those events north of the river into direct line with ‘our’ Thomas, ironmonger of Bermondsey, south of the river. My theory is that he started life as an apprentice Turner, and morphed into an Ironmonger outwith the City of London.

The records show that on 4 May 1726, a Thomas Meriton was apprenticed to his father Thomas, of the Turners Company, surely the same person as appeared in the marriage cited above. If these are ‘our’ Thomases, the younger would have been about 16, which was a possible age for an apprentice to begin his seven years of apprenticeship. If my theory is right, young Thomas would have completed his apprenticeship sometime in the 1730s, but I do not believe he did. ‘Our’ Thomas married Sarah Wilkinson in 1831, when our putative Thomas would have been about 21. Her father, George Wilkinson was an Ironmonger, and it seems possible that he might have helped to finance his new son-in-law’s ironmongery business south of the river. ‘Our’ Thomas shows no sign of becoming a Turner, but we will see further Turner connections as the years pass.

Moving to baptism records for the children of Thomas Meriton (1710-1765) and Sarah (nee Wilkinson) Meriton, we find little to help us. I now have nine possible offspring, most identified through marriage records and their parents’ Wills. Not a baptism record to be found! Here again, though, apprenticeship records help us on our way. The first ones are intriguing, introducing us to a hitherto unidentified son Thomas, and also to the mysterious Bart. They are as follows:

1 January 1752 Bart Meriton, son of Thomas, Bermondsey Surrey, Ironmonger, to Thomas Fowell, Turners’ Company.

5 February 1752 Thomas, son of Thomas Meriton, Bermondsey, Surrey, Ironmonger, to Thomas Fowell, Turners’ Company.

No ages are given. Were they twins? What happened to them? Of young Thomas I can find no further definitive trace. Of Bart we have seen in a previous post that his father in rather curmudgeonly tones left him ‘one annuity or yearly sum of £25’ to be paid by his wife as she saw fit for Bart’s support and maintenance, and there was to be nothing further, for ‘sufficient reasons’. I have then identified a marriage for a Bart Meriton to Mary Baker in Warwickshire on 2 February 1766, a year after ‘our’ Bart’s father died. Is this ‘our’ Bart? There is no further sign. He is not mentioned in his mother’s Will. (As an aside, I believe his name ‘Bart’ might have been linked to the married surname of George Wilkinson’s second wife, Sarah Bart. But I have nothing more about her.)

Note above, that Thomas and Bart were apprenticed to Thomas Fowell (or ffowell). I infer (hopefully correctly) that he is the person mentioned as ‘my cousin’ in Thomas Meriton’s Will, proved in 1765, and also receiver of a small legacy as Thomas ffowell, Merchant, in George Wilkinson’s Will (1768). Furthermore, Thomas ffowell is to become trustee and guardian of the under-age Meriton children should Sarah [nee Wilkinson] Meriton die before they reach 21. But he died just three years after Thomas Meriton, having mentioned ‘cousin Thomas Meriton’ in his Will (proved 16 August 1768) which showed he was seriously rich, with properties in Coleman Street, London, St Petersburg and Epping Forest, plus legacies of very many thousands of pounds to very many people! In the event, his wife Sarah (nee Dudds) pre-deceased him by two years, and their daughter Sarah Buxton profited handsomely as a result, along with very many other legatees, including a modest £ 200 to ‘my cousin Sarah Meriton, widow of Thomas Meriton’.

Am I right in inferring that Thomas Fowell, Merchant, died 1768, is one and the same as Thomas ffowell of the Turners Company? I don’t know. Suffice to say that either he or they played a significant part in the Meriton saga. A further Meriton son was apprenticed to Thomas Fowell of the Turners Company – Henry, on 3 February 1762. He would go on to become free of the Ironmongers Company by redemption (paying a fee). Thomas’ (1710-1765) brother John (1707- ?) was also apprenticed to his father Thomas, Turner, and became Master of the Company in 1749. Further family links with the Turners.

One final conjecture – the father of Thomas Meriton bap 1710. Could he be the Thomas Meriton, son of John Meriton, Citizen and Girdler, apprenticed on 7 Feb 1693/4 to Thomas Jorden, Turners Company? I think it seems likely. These dates would mean that the apprenticeship would have been completed by the time of the marriage to Elizabeth Howson in 1700. I have found nothing about John the Girdler!

Any comments/observations on these thoughts are more than welcome. In the meantime I am going to go along with my theory and add these older Thomas Meritons to my tree.